|

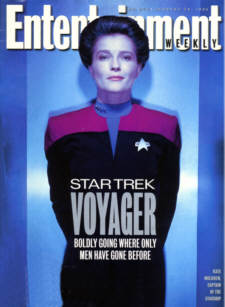

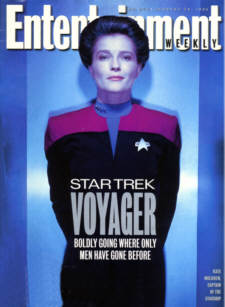

January 20, 1995 STAR TREK VOYAGER Boldly Going Where Only Men Have Gone Before |

|

January 20, 1995 STAR TREK VOYAGER Boldly Going Where Only Men Have Gone Before |

|

A New 'Trek,' A New Network, A New Captain--And (Red Alert!) She's A Woman By Albert Kim |

|

Mulgrew smiles and rebalances the packages in her arms. “That’s all right, doll. I already got mine.”

Indeed, for Mulgrew, Christmas had come three months earlier. That was when she was cast as Voyager’s Capt. Kathryn Janeway, the linchpin role in what may very well be the most anticipated TV series since, well, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine two years ago. But back in early September, the mood on the set wasn’t exactly one of glad tidings. Up to that point, Voyager had been beset by production delays, internal squabbling, and casting problems—problems that had climaxed when French-Canadian actress Genevieve Bujold was given the part of Janeway, only to bail out after two tempestuous days on the set.

Such troubles are commonplace for many new series, but the stakes are seldom this high: Voyager is the third spin-off in— and heir apparent to—the staggeringly profitable Trek empire, a franchise that has generated an estimated $2 billion in revenue for Paramount. In addition to TV, Trek has scored with movies, books, and merchandising products of every variety. That kind of bankability led the studio to choose Voyager as the centerpiece of its new United Paramount Network, which launches Jan. 16 with Voyager’s two-hour premiere. No wonder it seems all eyes in the universe are trained on what Paramount hopes will be the next Next Generation.

That places Mulgrew—who, as Janeway, becomes a successor to Trek icons James T. Kirk and Jean-Luc Picard—not only in the captain’s chair but also squarely in the proverbial hot seat. “Kate has a lot of pressure on her" says Robert Beltran, who plays Chakotay, the ship’s Native American first officer. “There’s really no precedent for her situation. Except maybe Joan of Arc.” He smiles. “And she had the anointing of God.”

“A female captain has a lot of leeway that a male captain wouldn’t have,” says Mulgrew, sitting in her trailer between scenes and methodically working her way through a pack of cigarettes. At 39, Mulgrew, a self-described “television beast,” is a veteran of innumerable TV campaigns, including a short stint as the title character in the NBC series Mrs. Columbo. With her clear Irish features and throaty, resonant voice, she bears an eerie resemblance to a young Katharine Hepburn. “Women have an emotional accessibility that our culture not only accepts but embraces. We have a tactility, a compassion, a maternity— and all these things can be revealed within the character of a very authoritative person.”

But Trek has not treated authoritative women kindly. Thirty years ago, after watching the original Trek pilot, NBC executives ordered creator Gene Roddenberry to eliminate the female first officer because she seemed too threatening. (The actress, Majel Barrett, was eventually recast as Nurse Chapel, and later became Roddenberry’s wife.) It was downhill from there for Trek feminists. The final episode of the original series, “Turnabout Intruder,” found the character of Dr. Janice Lester railing at the indignities of a chauvinistic Starfleet that didn’t allow female starship captains. The situation became a little more equitable in The Next Generation, which featured women in command in several stories. But most of them, like Capt. Rachel Garrett of the Enterprise-C, contracted Trek’s dreaded red-shirt syndrome: an untimely death within the first half hour.

“It took balls for these guys to hire me in this capacity,” says Mulgrew, the first woman to lead a Trek series onto TV. “It’s a bold choice, and an appropriate one for 400 years in the future.”

But casting a woman to helm the ship is only one way Voyager ventures into new territory. There’s also the show’s premise: Janeway, in command of the newly commissioned U.S.S. Voyager, sets out to track down a rebel group known as the Maquis when a strange galactic phenomenon (that hoary Trek staple) flings both the Voyager and the Maquis ship into the distant reaches of the galaxy—so distant that at maximum warp, it would take them 70 years to return home. The two crews put aside their differences and band together to find a way back. On the journey, they will presumably encounter strange new worlds and new civilizations—and freaky new aliens to turn into hot-selling action figures.

The formula is Trek through and through: a warp-speed-paced, ship-centered show with a setup that allows for both weighty philosophical reflection and zesty shoot-’em-ups—a tale equal parts Lost in Space and The Odyssey. ‘We are cutting our ties with a part of the universe that our audience is very comfortable with,” says coexecutive producer Jeri Taylor. “No more Klingons, or Romulans, or Cardassians. The Federation is 70,000 light-years away. We are taking all of that away and starting from scratch.” Adds coexecutive producer Michael Piller, “You go back to the original show in the ‘60s and the spirit of that was: one ship with a bunch of people, out there alone, exploring the unknown, never sure what they were going to find around any corner. That’s what we wanted, so that Voyager wouldn’t be just a pale imitation of The Next Generation.”

Implicit in that assessment is the desire not to repeat the mistakes of Deep Space Nine. When it premiered in 1993, DS9 was the designated successor to The Next Generation’s throne. But the show stumbled through its first season, hampered by underdeveloped characters and mundane storytelling. Trekkers cited DS9’s flawed premise-a stationary stage for characters in perpetual conflict-which they felt betrayed the Trek ideal of cosmic exploration and universal harmony. “It’s just a bunch of guys in a building yelling at each other,” says one Trek insider.

With DS9’s lessons in mind, Voyager’s early episodes will quickly try to establish the dynamics of its crew by throwing every tried-and-true Trek trick in the book at them: space anomalies, time warps, funky predatory aliens, etc. Yet the producers remain cautious. “Voyager will not have the same ratings that The Next Generation had,” says Piller. “It just won’t. I don’t think even the studio expects that.”

What the studio does expect, unequivocally, is a hit. Over the course of its seven syndicated seasons, The Next Generation raked in an estimated $511 million in revenue for Paramount— a major factor in convincing executives of the viability of a new network centered around a new Trek. “There’s a great deal of pressure on us,” says Taylor. “Affiliates were drawn into the fold by the prospect of getting Voyager. We know the expectations are inordinately high.”

Which is why a number of executive eyebrows were raised when the creative troika of Taylor, Piller, and coexec producer Rick Berman insisted that Voyager be helmed by a woman. Trek’s strength has always been with males ages 18 to 49, the same group the new network targets as its core audience. For this demographic, The Next Generation had been the No. 1 show on the air; bar none. So when Voyager’s producers made it clear their new show would star a woman (“It seemed like the logical thing to do,” says Berman, echoing a famous first officer), the question became, Would Trekkies have responded as enthusiastically to Capt. Jane T. Kirk, or Capt. Jeanne-Marie Picard?

Fans were quick to answer. “Why oh why would the producers put a woman in charge of Voyager?” wrote one distraught America Online subscriber. “Do they want it to sink? What they need is a Kirk-type: strong, ambitious and full of testosterone.” Some postings were even more succinct: “The show will suck because of the woman.”

Paramount didn’t turn a deaf ear to such sentiments. According to one source, the studio angrily demanded that the captain’s role be changed to a man—a report Berman wholeheartedly denies. “I told them, ‘I want to do this with a woman,’ and they were very supportive,” says Berman. “They just said, ‘Let’s not close the door to men. Look at men as well.’ But being opposed to a woman—that’s nonsense. They just weren’t 100 percent sure we would find the right woman.”

Berman himself must have had doubts—hundreds of actresses were auditioned last summer. Among those reportedly under consideration: Kate Jackson, Lindsay Wagner, Tracy Scoggins, Linda Hamilton, even Patty Duke. Not until Sept. 1, the date shooting was supposed to begin, was a decision announced.

“I have a great urge to tip my hat to a large group of people who understood the financial and commercial importance of making the absolute right choice of captain,” says Mulgrew. “And they then transcended that. They said, ‘This is what we really believe.’” Mulgrew pauses, clears her throat. “And they believed it should be Genevieve Bujold.”

Bujold arrived on the set on Sept. 7. By the end of the day on Sept. 8, she had turned in her Starfleet pips. Officially, the reason for her departure was that she was unable to handle the grind of Voyager’s 18-hour days. But unofficially, sources say that right off the bat, Bujold was as uncomfortable as a Klingon in a tub of Tribbles. She had problems with her wardrobe, her hairstyle, and even the notoriously difficult Trek technical dialogue. All this merely served to heighten tensions on an already strained set.

“There was this feeling of unease when we were working with her,” says Tim Russ, who plays the Vulcan tactical officer Tuvok. “I wrote it off to her getting started, but as it turns out, it probably would have been fairly consistent.” Adds Robert Duncan McNeill, who plays ship pilot Tom Paris: “She just didn’t fit. It was clear to everybody. Who knows why she chose to accept this job—maybe her agents convinced her to. But it was a wrong decision.” (Bujold declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Bujold’s abrupt departure created a new set of worries. “At that point, they said they were going to start looking at male captains as well,” says Garrett Wang, who plays Ensign Harry Kim. “That put a big scare into me because I interpreted that as, if they get a male, they’re going to have to add another woman for balance and ax a male crew member.”

Wang had reason to worry. Having nearly exhausted Hollywood’s supply of actresses and backed into another delay, Berman, Piller, and Taylor started reading men for the captain’s role and indeed considered recasting Chakotay and Kim as women. Meanwhile, Mulgrew was on her way to L.A. for a second audition. In the first go-around, she had submitted a tape made in New York, but it had gone poorly. (“It wasn’t clear in my brain what I was doing,” recalls Mulgrew. “Is this a series, is it a spin-off, is it a movie?”) After meeting with the producers, Mulgrew and three other actresses were presented to the network as the last batch of viable female candidates.

“They were tired, they were nervous, they were behind,” says Mulgrew. “They just closed the door and said, ‘Who looks strong? Who can stand up to this kind of pressure for seven years?” On Sept. 16, the producers finally thought they had the right answer—and announced Mulgrew.

“We were blessed to get Kate,” says Robert Picardo, who plays the holographic physician Doc Zimmerman. “We were nervous and, literally, a ship without a captain. It truly was the 11th hour.”

The Voyager crew is entering the 13th hour of production on this very long Tuesday, five days before Christmas, and Roxann Biggs-Dawson, who plays B’Elanna Torres, the ship’s temperamental half-Klingon/half-human chief engineer, is encountering difficulties with that most Trekkish of phenomena: technobabble.

“Vent a couple of LN2 exhaust conduits along the dorsal...” She pauses. Cut. “Vent a couple of LN2...” Cut. She blinks. “Vent a couple of LN2. .. .“

After she makes a half-dozen stabs at spitting out the line, director LeVar Burton—The Next Generation’s Geordi La Forge himself—bounds onto the bridge set and kneels in front of Dawson. He tells her to take a deep breath and relax, then casually chats, one chief engineer to another. A few minutes later, he steps off the stage and calls for action.

“Vent a couple of LN2 exhaust conduits along the dorsal emitters,” Dawson recites flawlessly. “Make it look like we’re in serious trouble.” Cut. Print. Biggs-Dawson lets out a whoop.

“Do I miss that?” says Burton later, relaxing between takes. “Nooooo, sir. I don’t have to get up at 6:00 a.m. I don’t have to get into a space suit. I don’t have to put on that VISOR. Miss it? No.” Burton shakes his head, then again: “No.”

But one thing that Burton will probably never escape is the crushing attention that all members of the Trek universe—past, present, and future—receive, something that’s already starting to overwhelm the Voyager crew. Fan mail has been pouring in for months, as have speaking offers from assorted conventions. Picardo has already been asked to appear at a Trek gathering…. .in Ireland. In 1996. Says Picardo: “I told them, ‘Gee, I think I’m free...’”

‘We haven’t even aired yet,” says Ethan Phillips, who plays the resident troll-faced alien, Neelix. “We’re getting interviewed, our pictures are being taken. It just doesn’t make any sense to me. I’m not really prepared for this.”

Chances are, Phillips will have a fair amount of time to acclimate himself to the attention. Burton’s presence on the set is also a symbolic reminder of how far Voyager could go. Just as The Next Generation successfully sailed onto the wide screen after seven fruitful seasons, so could this new generation find itself admiring its opening weekend grosses, say, in the year 2002.

“Does the prognosis look good to me?” muses Picardo, sounding like the doctor he plays. “Yes, it does. I am definitely looking forward to the possibility that these characters could go beyond television. As an actor, I’ve never had a job like this, where you think in terms of something lasting that long.”

Considering the travails Voyager has already endured,

such optimism is nearly warranted, particularly if you take into account

the track record of the franchise involved. Or as Beltran, the spiritually

tuned-in Chakotay, puts it: “We’re going to really have to suck to fail.”•

|

|