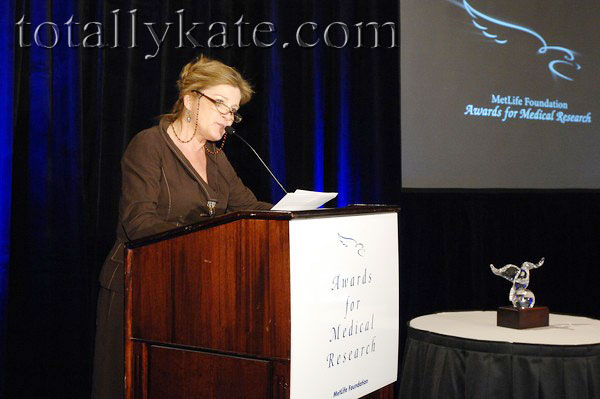

Video of Speech

Keynote speech by Kate Mulgrew

MetLife Foundation Awards for Medical

Research in Alzheimer's Disease

FEB. 29, 2008 - Washington, D. C.

I’d like to first thank the MetLife Foundation

for their extraordinary generosity to Alzheimer’s research. Apparently,

someone very high up understands the urgency that this disease inspires,

and has both the compassion and the wherewithal to act on it. I would

also like to congratulate the scientists who are being honored today, not

only for their accomplishments, but for their essence: they are the

rara avis. Against all odds, they persevere, and in so doing, save

us all.

I’m at a stage in my life where, finally,

I can accept that almost all experience is bittersweet- and I can accept,

too, the inevitability of death. I think I will neither fear it nor

welcome it, as long as I can face it squarely and with some dignity.

After all, we have no say over our entrance into this world – the least

we can ask as human beings is to go clear-eyed and honest into that good

night.

My mother’s name was Joan but everyone

called her Jiki. The bookends of my mother’s life reveal the full

irony of her story. Her own mother died in childbirth stamping my

mother, before she could even speak, with a wild hunger and a deep and

solitary grief.

These currents ran through my mother all

her life and, though they defined her, they did not deter her from living

the life she chose. She learned the gifts of passion and friendship

early on, and when she stumbled upon my father, she recognized a kindred

spirit, and so they ran off together and had eight children in quick and

alarming succession. I was her second born, her first girl and, as

she would later say (to the surprise and occasional horror of anyone who

would listen):”Kitten was my first daughter so, of course, she was my favorite

– she was the mother I never had.”

She buried two of her eight children when

they were very young; Maggie, as a baby, and Tessie, of a brain tumor,

when she was fourteen. This last was a mortal blow and nearly cost

my mother her marriage and her sanity. She rallied, however, and

with Baruch Spinoza as her mentor and art as her creative furnace, she

became a celebrated painter, a maverick personality, a remarkable example

of grit and depth, wit and daring – we all loved her quite madly.

For her 70th birthday, I took my mother

on a cruise up The Aegean Sea. One night, looking at the Turkish

moon and drinking Irish whiskey, she wanted to talk about sadness.

She told me that the greatest sorrow of her life was that she had never

stopped searching for her mother and, whereas she knew this was emotionally

irrational, she could manage it as long as she was intellectually sound.

“My brain is the superior organ, and it gives me all my happiness,” she

said. “I can read, paint, play the piano, laugh at your father, I

can think and I can love. Want to know how special the brain is?”

she asked, pointing to the sky. “I can see the moon, but the moon

can’t see me.”

A month later, she was diagnosed with atypical

Alzheimer’s disease. She begged me to help her find a way out of

the nightmare but, of course, I didn’t. I couldn’t. You understand.

Instead, I just watched. I watched

as my father, furious with denial, slowly disintegrated, until one day

he crawled into his bed and died there, two weeks later. Cancer,

they said, cancer everywhere – in his lungs, in his chest, on his brainstem.

I watched as my siblings, once so funny

and charming and irreverent, grew confused and suspicious and, unable to

sever the bond they had always known with their mother, severed it with

one another, instead.

I just watched. Of course, I was

dutiful and vigilant. I learned how to change her diapers, how to

bathe her, how to put the spoon to her mouth. I did all of this with

a smile and studied, stupid expressions of affection.

One day, eight years after her diagnosis,

she simply refused the spoon – and shortly afterward, she refused the water.

But even then she held on as, one by one, all of her children embraced

her and bade her good-bye.

I was the last to kneel by her side and,

looking into her eyes, I gave her a walloping dose of morphine and, as

I cradled her head in my arms, I wept and begged her forgiveness – because

I had born witness to this final mortification. My mother died with

her eyes wide open – unseeing, senseless, and without a shred of dignity.

It looks like I may well be the genetic

heir to this same fate – that is, if I am truly my mother’s daughter –

and so I urge science, on behalf of my glorious and unexpected mother,

to work hard and demand much and strive passionately to control this disease,

so as to spare my own sons the ultimate mortification of having to bury

a mother whom they love deeply but who, herself, no longer knows or cares

what love is.

Speech reprinted in the Summer 2008 issue

of Preserving Your Memory magazine - download

pdf |